A brief history of American food monopolies

A guest post by John Klar

Do you ever wonder why food prices can climb so quickly, and you have no choice but to pay or go without?

The answer is that a cartel, a small number of large corporations, controls almost every aspect of our food supply, from the feed and equipment used in farming to the animals and farmers themselves. Most of the animals being raised in swine and chicken operations are owned by corporations, not by the farmers who care for them.

Grocery prices will continue to increase as food companies tighten their grip on our most essential need: food.

The industrial system hidden behind grocery shelves

Dairy, pig, and chicken farms have been taken over in recent decades, turning farmers into contracted serfs with no power over their own livelihoods. Federal subsidies support the largest crop farmers – especially those that produce soy and corn – which primarily fund the chemical companies that manufacture the Roundup and pesticides that these crops depend on. These chemicals end up in our children’s school lunches!

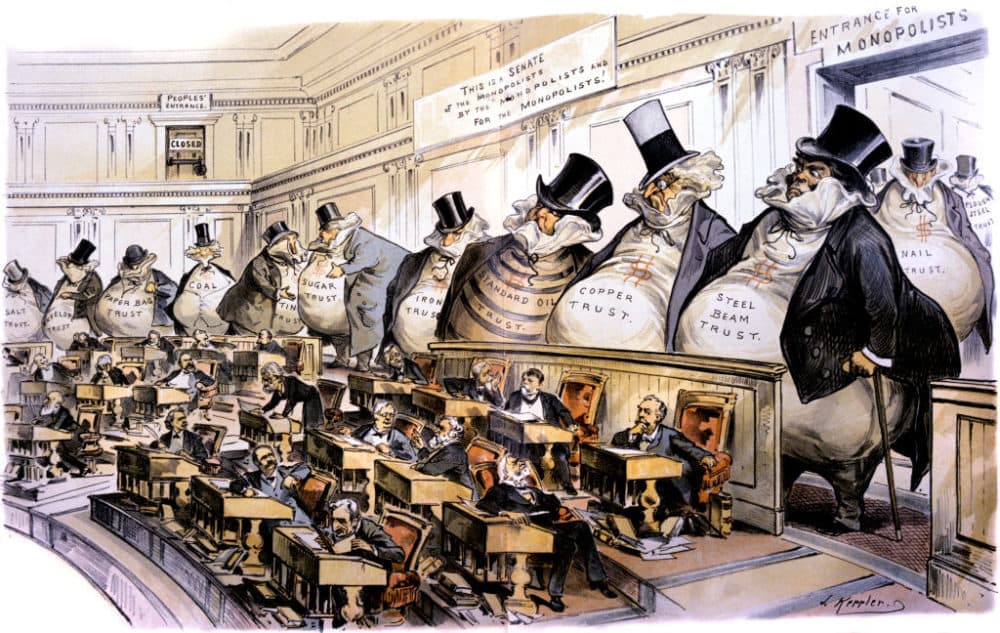

There is a long history of wealthy corporations and trusts in the United States taking over food supplies for profit. When companies acquire small businesses, fix prices to harm other firms, and consolidate entire segments of production, it is referred to as a monopoly, which is defined as “a company or group having exclusive control over a commodity or service.”

Often, the same companies control the supply chain of materials to the farmer, then control the farmers through processing, and finally distribution to the grocery store customer. This is called vertical integration. Wal-Mart is an example of this pattern of controlling different stages of production. The company has acquired multiple smaller enterprises, allowing it to own many farms that supply its milk and meat, and it also owns meat processing and distribution operations. This one company can control the whole system (for some of its products), and Walmart can use this market power to increase prices to consumers, as well as lower the prices it pays to farmers.

Horizontal integration describes a different kind of market control through monopolization, where one or a few companies gobble up their competitors. For example, only four companies now control 85% of the beef slaughter and processing capacity in the United States. These four companies can collude on how much to pay for cattle, and independent ranchers don’t stand a chance against them.

Hidden from view in your local grocery store is a vast industrial system that has steadily replaced farmers with machines and large companies that control almost every morsel of your food. These companies are now multinational monsters who have the power to decide what humans will be allowed to eat in the future, and what it will cost.

When government looks the other way

The federal government does have the power, using antitrust law, to break up large monopolies. But our regulatory agencies have remained silent over the last few years as a Chinese company became the largest supplier of pork and a Brazilian company became the largest supplier of beef in the US. This is always the case when markets are unregulated – the big swallow the small, over and over, and a monopoly or cartel can be established very quickly.

The 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act made it a criminal felony to “monopolize any part of trade or commerce,” but its provisions were soon watered down by courts influenced by big corporations and J.P. Morgan. The “Great Merger Movement” of 1895-1904 followed, during which the consolidation of tobacco, meat processing, farm equipment, and other agricultural industries occurred. Large trusts and companies created monopolies that controlled every aspect of food production.

Although the government began to respond to these abuses, the advent of World War I temporarily halted anti-monopoly measures as the country increased food production to feed a starving Europe. When the war ended, crop prices plummeted due to overproduction when overseas markets were lost. Abusive practices by the entrenched monopolies ensured that equipment, fertilizer, and other farm input costs remained high. The Great Depression then ensued. Americans struggled to afford food while 750,000 family farms failed between 1930 and 1935 – a quarter of all the nation’s farms.

The FDR Administration learned from this failure: the nation did not permit monopolies to run rampant during World War II. On the contrary, the Antitrust Division scrutinized cartel arrangements between American, German, and Japanese companies that used unlawful practices to dominate markets for phosphate fertilizers, nitrogen ammonia, and other chemicals.

The federal government vigilantly sought to protect small businesses from domination by big business from the late 1930s through the early 1950s. Competition increased for pesticides, fertilizers, electricity generation, meat and grain processing facilities, and farm equipment. This effort functioned effectively to prevent widespread farm failures into the 1980s.

How monopoly power hollowed out rural America

Then the Nixon and Ford administrations pursued deregulatory policies that undermined competition in agriculture, reverting to the pro-monopoly farm and antitrust policies of the 1920s. This accelerated under the Carter and Reagan administrations, which both allowed rapid consolidation in the nation’s food system and abandoned the supply management programs that had shielded crop prices from rapid decline. Reagan’s Food Security Act expanded federal price supports for commodity crops that farmers grow, but this favored large farmers. Crop prices continued to plummet under the Clinton administration’s “Agricultural Improvement and Reform Act of 1996,” which pushed farmers to grow more monoculture crops.

In the early 1970s, Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz infamously declared to farmers, “Get big or get out!” Small farms were decimated: by the end of the 1980s, nearly 300,000 mostly small farms (less than 500 acres) had vanished, a sixth of the country’s farms.

Who captures the food dollar — then and now

In 1970, before this massive industry consolidation, 70% of the market price for beef went to the ranchers who put in the sweat to raise them. Today, ranchers receive only 30% of the price paid by consumers. No wonder so many have gone out of business. Grocery store chains have been hit by the same consolidation: 75% of shoppers now purchase groceries at Walmart.

These consolidations also encouraged Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), in which animals are fed antibiotics and grains and confined to indoor facilities. Sprawling “feed lots” now produce the majority of US beef. Dairy farms have similarly consolidated, forcing cows into indoor facilities where they never walk on pasture. Swine and chicken (for both layers and meat birds) farming similarly industrialized.

Monopolizing companies often control prices for animal feed, bedding, fertilizers, and pesticides in addition to the animals themselves – they supply chicks and piglets to contracted farmers. This forces farmers to become contracted serfs with no control over what they receive for the animals they raise. Similar consolidation in crop farming has resulted in vast operations growing only a single crop (especially corn, soy, wheat, or cotton) for industrial purposes. Family farms continue to disappear.

Subsidies that reward scale, not stewardship

Today, two major farm subsidy programs (the Price Loss Coverage program and the Agricultural Risk Coverage program) channel most federal subsidies to large grain and oilseed agribusinesses, effectively excluding small-scale farmers and those who grow multiple crops. It ensures chronic overproduction of corn, soybeans, and other grain and oilseed crops.

Many large farms operate at a net loss, selling commodities at a price below their cost of production, because federal subsidies offset their losses, and have become their true source of profit. Smaller family farms cannot compete: between 2017 and 2024, 142,000 more farms went under: that’s 7% of all US farms.

Meanwhile, Americans are buying foods controlled “from soup to nuts” by an ever-smaller cabal of ever-larger corporations. The monopolization of agriculture has returned with a vengeance, eliminating farms and backyard gardens alike from the American landscape and creating a dangerous dependency on processed foods made from commodity crops.

What can be done — by eaters and by government

It is imperative that the federal government champion the antitrust legislation of a century ago to enhance competition, promote fairness, and preserve family farms and rural landscapes. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have played a leading role in alternately relaxing or enforcing these laws over the last century. These agencies must lead an antitrust revival to scrutinize the handful of companies that now dominate the nation’s entire food supply.

Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division at the DOJ, Gail Slater, is reportedly “deeply committed and believes aggressive antitrust enforcement can benefit consumers in countless ways.”[1] Existing antitrust laws and regulatory powers permit her office and the FTC to pursue relief.

A tiny number of global corporations now control the lion’s share of all human food in the US,[2] as well as the means to grow crops and meat. The World Economic Forum claims that to save the planet from climate change, humans will have to give up meat and adopt a plant-based diet, consuming only plants and bugs. This is propaganda, designed to support yet more consolidation and monopolization of agriculture. What we need instead are regenerative practices to restore the soil, and grazing animals on the land is an essential part of this restoration.

Americans and their local farms are fighting for their lives, liberties, and the pursuit of happiness in the real world. Small businesses, family farms and restaurants, corner grocery stores, and local food processors and manufacturers are the foundation of a resilient economy, bustling communities, and healthy families.

Americans can fight back by buying directly from farmers or local businesses whenever possible, including through farm shares, also known as Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs).

The federal government has a vital role to play in enforcing antitrust laws that prohibit underhanded business practices and disallow monopolies. State and federal government agencies can also reduce excessive regulations that harm small farmers, and support small farms by providing subsidies fairly, regardless of farm size.

American eaters and American farmers must unite to oppose the agricultural market monopolization that threatens the health, liberty, and wealth of all Americans.

For more detailed information, read FarmAction‘s excellent report on monopolization in the meat industry.

[1] Lydia Moynihan, “Antitrust enforcer Gail Slater on American innovation: ‘We can win the AI race against the Chinese without becoming like China’,” New York Post, July 3, 2025.

[2] “The Economic Cost of Food Monopolies: The Grocery Cartels” — Food & Water Watch. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/2021/11/15/as-food-prices-soar-new-report-details-vast-grocery-industry-consolidation-crisis/