Grocery Store Consolidation

“Up until the 1980s, almost every small town in North Dakota had a grocery store,” wrote Stacy Mitchell, of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) for The Atlantic. “Many, in fact, had two or more competing supermarkets. Now nearly half of North Dakota’s rural residents live in a food desert.”

This means the vast majority of America’s farmers who grow the food we eat not only lack access to the marketplace to sell what they produce, but they often do not have access to a nearby grocery store for their own families. America’s farmers are being required to transport their products further, while also driving further just to meet their own basic needs, due to the deepening impacts of consolidation.

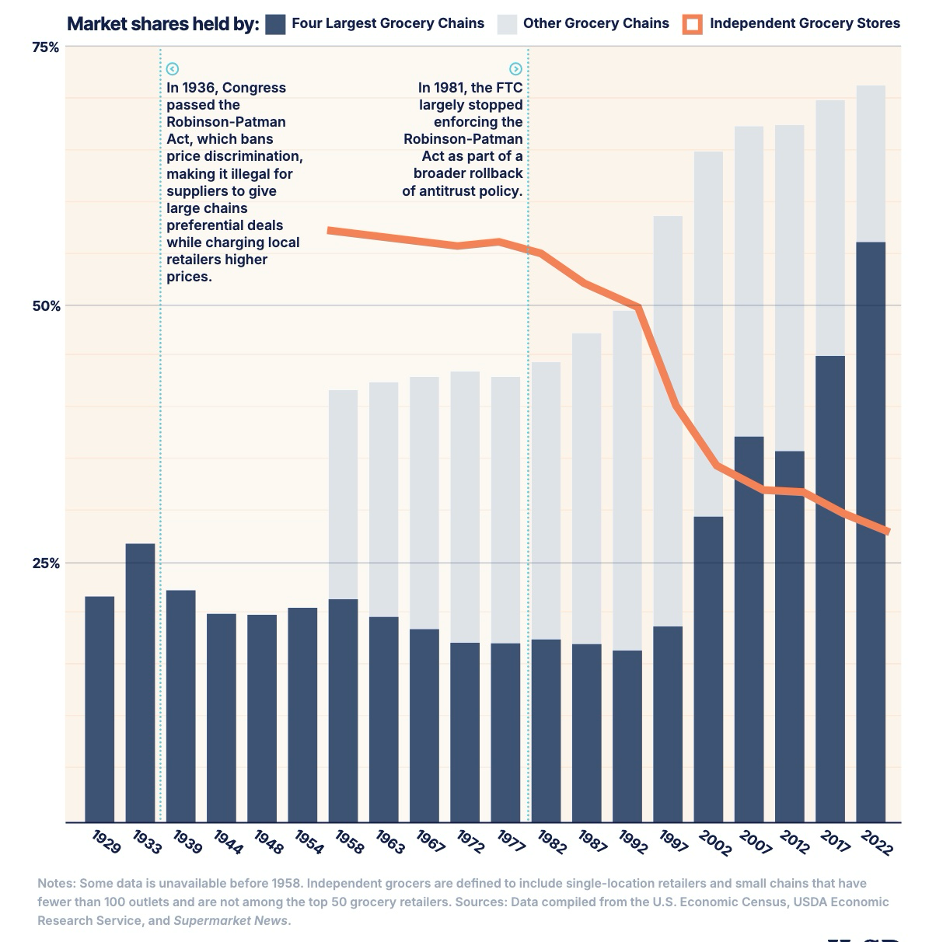

According to data from the ILSR, this consolidation of grocery stores can be directly linked to a lack of anti-trust law enforcement.

By Stacy Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR)

For decades — from the 1930s until the 1980s — the U.S. grocery industry was remarkably competitive, with independent grocers thriving alongside large chains like Kroger and Safeway. Independent stores consistently accounted for more than 50 percent of U.S. grocery sales throughout this period. Meanwhile the four largest chains collectively captured only about 20 percent of the market.

This rich diversity served communities and consumers well. Virtually every neighborhood and small town had a grocery store, and many had several. Farmers could sell to their local stores.

Then, in the early 1980s, the government stopped enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act, a critical antitrust law that prohibits price discrimination by suppliers. This enabled grocery chains to make special deals with suppliers, using a variety of anticompetitive methods to price out independent groceries and create local monopolies or cartels. The consequences were swift and far-reaching: independent grocers declined rapidly, and a few large retailers gained dominance. Food deserts and higher prices followed.”

https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ILSR-GroceryMarket-Graph-Final.pdf

New data from ILSR highlights the direct link between the decline in Robinson-Patman enforcement and the collapse of independent grocers — a clear example of how policy decisions shape our communities and everyday lives.

According to Science in the Public Interest,

“Last October, Kroger and Albertsons announced a planned merger that would create a single entity that could control 22 percent of the U.S. grocery market—second only to Walmart’s 25 percent share of U.S. grocery purchases.

The store chains affected by the proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger include Ralphs, Dillons, Smith’s, King Soopers, Fry’s, QFC, City Market, Owen’s, Jay C, Pay Less, Baker’s, Gerbes, Harris Teeter, Pick N’ Save, Metro Market, Mariano’s, Fred Meyer, Food 4 Less and Foods Co.—all controlled by Kroger—and Safeway, Vons, Jewel-Osco, Shaw’s, Acme, Tom Thumb, Randalls, United Supermarkets, Pavilions, Star Market, Haggen, Carrs, Kings Food Markets and Balducci’s Food Lovers Market—all controlled by Albertsons.

That’s a long list. And the outlook for grocery consumers—that is to say, all Americans who shop for food—is not great. Writing for the Los Angeles Times in 2018, David Lazarus’s column (bearing the headline “When companies say a merger will result in lower prices, try laughing in their face”) summed up how corporate anticompetitive and anticonsumer maneuvers affect all of us:

“We’ve seen it again and again — in the phone industry, the cable industry, the drug industry, the insurance industry, the banking industry, the oil industry. Companies merge, prices go up, service declines.”

As Angela Huffman of Farm Action noted,

“As mega-retailers like Walmart and Dollar General expand across the country, independent grocers and farmers are driven out of business, consumers pay more, and communities are left with fewer jobs and decreased access to nutritious foods.”

While the solution is to enforce the U.S.’ antitrust laws, only the government can do that. It is up to us to say enough is enough. If we don’t want there to be only one company left in the U.S., our government needs to take our anti-trust laws seriously.