Restricting Local Meat

The biggest obstacle to a prosperous local food system in this country is the lack of slaughterhouse infrastructure. In 1967 there were around 9,600 slaughterhouses in the U.S. [1]; today, according to USDA, that number stands at around 3,000 [2]. Most of these are not USDA-inspected, and therefore any meat processed in them cannot be sold beyond state lines (for state-inspected facilities) or cannot be sold at all (if processed in local, small custom facilities). There are a few rare exceptions.

The approximately 1000 USDA-inspected meat processing plants and 1850 plants that are not federally inspected. There are not enough USDA plants to process all the livestock. As a result, many small farmers and ranchers have trouble finding an available facility to slaughter and process their livestock and poultry.

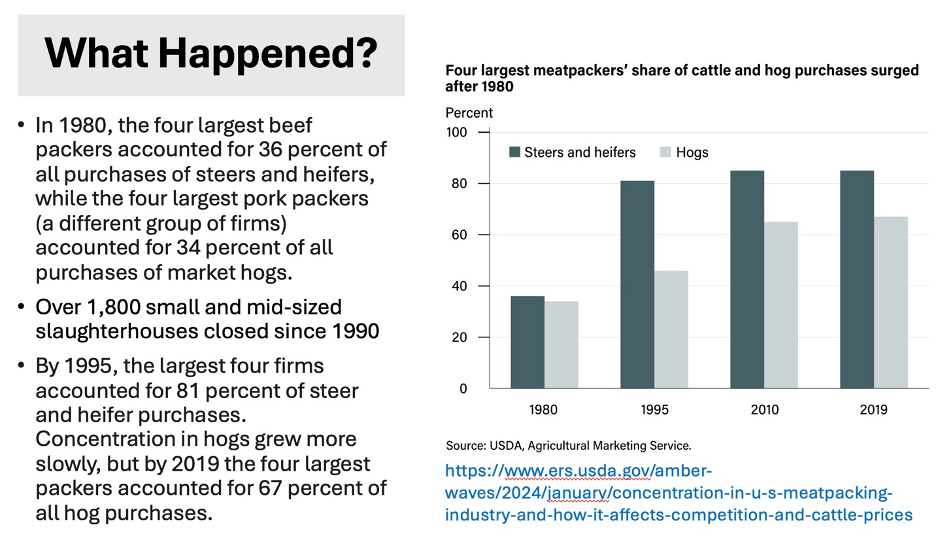

The main cause of this problem is the 1967 Wholesome Meat Act (WMA), one of the worst pieces of food legislation Congress has ever passed. Before the WMA there was a competitive meat industry in this country. Today there are oligopolies in beef where four meat packers control 85% of the market and in pork where four meat packers control 67% of the market [3].

The high cost of compliance with the WMA drove thousands of community slaughterhouses and butchers out of business.

The WMA amended the existing Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA) so that federal law preempts any conflicting state law on slaughter, processing, and sales of meat. The WMA prohibits the sale of meat in both interstate and intrastate commerce unless the facilities slaughtering and/or processing the meat are in compliance with the FMIA–meaning, among other things, that an inspector must be present when slaughter and processing are taking place.

A custom meat processing facility can slaughter and process without an inspector being present, but the meat cannot be sold by the owner of the processed animal or the custom facility. The owner, in turn, can only distribute that meat to his family, nonpaying guests, and employees. Under the FMIA, any meat from an animal slaughtered on a farm can only go to those same parties; as with custom slaughter, there is a prohibition on selling the meat–unless a consumer has already purchased a herd share prior to slaughter–in which case he can collect the meat he purchased while the animal was alive. Some states allow this while others do not.

The consolidation in the meat industry has led to a situation where the 12 largest slaughter plants account for 51% of total cattle killed, and the 15 largest plants account for 64% of the total hogs slaughtered [4]. The largest plants slaughter and process several thousand cattle and 8-10,000 hogs a day, leading to a high rate of injuries in the workers, and deterioration in food safety and quality. At the same time, the lack of slaughterhouse access for small farmers and ranchers has made them unable to meet the growing demand for grassfed meat.

One partial remedy for the problem is the Processing Revival and Intrastate Meat Exemption Act (PRIME Act), legislation introduced by Congressman Thomas Massie, that would give states the option of allowing the intrastate sale of meat from animals slaughtered and processed at a custom facility. A version of the PRIME Act made it into the 2024 House Farm Bill. The current version has 9 Senate Sponsors and 45 House sponsors.

Rolling back the Wholesome Meat Act, strengthening local slaughterhouse infrastructure, and decentralizing meat processing are essential for:

a) small farmers and ranchers to remain in business and meet the demand for high quality meat, and

b) consumers to be able to access local, high-quality meat with known provenance.

Consider supporting the PRIME Act or other legislation that supports the accessibility of local food.

Sources

1. United States Small Business Administration and United States Congress. Senate. Committee on Small Business. (1971). The Effects of the Wholesome Meat Act of 1967 Upon Small Business: A Study of One Industry’s Economic Problems Resulting from Environmental-Consumer Legislation. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

2. United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2025, April). Livestock Slaughter 2024 Summary. p. 62. Posted at

3. Ibid. p. 4

4. Ibid.