Hog Industry Consolidation

https://foodprint.org/reports/the-foodprint-of-pork/

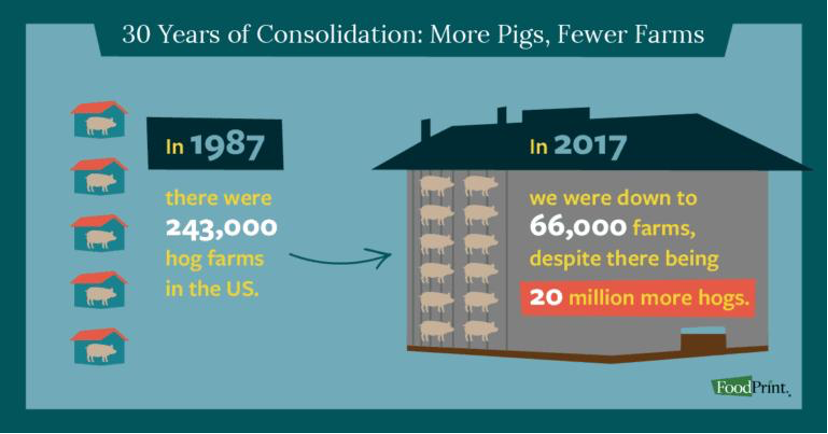

Similar to the poultry industry, the U.S. hog industry has become almost entirely consolidated and owned by large corporations in a mere 30 years.

Between 1987 and 2017, 73% of hog farmers went out of business. Large-scale indoor operations, known as Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), now dominate the industry. Meanwhile, just four corporations, including China’s Smithfield, accounted for 67% of the total U.S. hog production in 2023. [1]

In addition to driving independent farmers out of business, CAFOs are a real danger to the environment. Current HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. explained some of the damage historically caused by factory hog farms, which he had once litigated against:

“A spill from one pig lagoon killed a billion fish in North Carolina’s Neuse River in 1995. Bulldozers had to be used to plough the dead fish clear. Today 100 million fish die in the river every year…. The Smithfield style of industrial pork production is a major source of air pollution and probably the largest cause of water pollution in the US.” [2]. Smithfield is the largest pork producer in the US, and was purchased by a Chinese company in 2013.”

But how did we get here?

The hog industry’s consolidation has occurred through a series of by power grabs, undercutting prices at a loss to take over the industry in North Carolina, as exposed by Secretary Kennedy Jr. in this video. [3]

“The only farmers who could stay in business were farmers that signed a contract, they mortgaged their homes to put the Murphy 1100s [hog houses] on their property and they lost all control.”

Smithfield dictates everything — feed, piglet breed, and slaughter — turning farmers into indentured servants.

These small farms and mega-farms, controlling over 60% of U.S. hogs, prioritize profits by raising breeds that grow large quickly, such as the Yorkshire.

Rather than breed for health traits, or strong immune systems, just three breeds dominate the industry. In order to offset the risk of illness from overcrowding and lack of breed diversity in their hogs, and to encourage hogs to maintain muscle weight, hogs are routinely fed low doses of antibiotics. [4] They are also fed waste products — including candy waste.

This combined practice of overcrowding and administering low doses of antibiotics has led to antibiotic resistance in the bacteria present in the hogs’ intestines, which often contaminate the meat. [4] Researchers have linked antibiotic resistant bacteria in the gut of cattle and hogs to increased cases of antibiotic-resistant human infections. [4]

The rising risks of these conditions has been met with the rapid approval of new, untested vaccines.

The company Harrisvaccines received a conditional approval in September of 2015 to develop a first of-its-kind technology for animal flu viruses, which are known to mutate quickly. That technology, quickly acquired by MERCK Animal Health for use in hogs, is known today by its commercially available name, SEQUIVITY. [5]

SEQUIVITY, an mRNA platform, begins as a private contract directly between the hog owner and MERCK. When hogs become ill, the hog owner sends a sample from the hog to MERCK. Using computer modeling, MERCK creates a batch of mRNA vaccines, unique to this sample and never previously tested, hoping it stops the virus. This is why it’s called a platform, rather than a vaccine.

Consolidation of the hog industry has not only helped to fast-track these new types of risky interventions, with unknown human impacts when the pork is processed or consumed, it has also crushed independent farmers that offer an alternative option to the practices used by monopolistic producers.

Small farmers, unable to compete with corporate factory farms, face bankruptcy or buyouts — reducing consumer options and choices.

Meanwhile, industrial farms are terrible neighbors and disproportionately harm the rural communities in which they operate in. [6]

From polluted waterways to health and economic impacts, the costs of industrial hog farms are paid by consumers, rural communities, and contracted farmers [6], while companies like Smithfield reap millions in government subsidies. [7]

The solution lies in decentralizing production and expanding market access for independent farmers — instead of developing a pipeline of novel livestock pharmaceuticals.

Supporting diverse, small-scale farms enhances breed variety, reduces disease risk, and bolsters local economies.

Policy must shift to favor independent producers, limit antibiotic overuse, and enforce environmental accountability.

Without action, further consolidation could soon lead to a point of no return.

For more information:

Sources:

1. https://nffc.net/what-we-do/ending-corporate-control/

2. https://theecologist.org/2003/dec/01/smithfield-foods-truth-behind-its-pigs-and-

factories

3. https://youtu.be/08RXal8XTm4?si=t4kOiVL0rDcKqepc

4. https://pitjournal.unc.edu/2023/01/13/our-food-insecurity-the-overuse-of-

antibiotics-in-hog-production/

5. https://www.merck.com/news/merck-animal-health-to-acquire-harrisvaccines/

6. https://agworld.io/beneath-chinese-ownership-smithfield-foods-faces-scrutiny-for-

pollution-and-price-fixing-issues/

7. https://essfeed.com/top-10-meat-brands-benefiting-from-government-subsidies/